Havana Glasgow Film Festival are very pleased to present a programme of new feminist short films made as part of an initiative spearheaded by David Archibald from the University of Glasgow and Núria Araüna Baró of Universitat Rovira in Virgil, Catalunya, who are working with the festival and feminist activists and organisations to use AV technology to amplify women’s voices from Low and Middle Income Countries. The aims of the project are to encourage transnational experience sharing between the Global South and the Global North, and build networks of support and solidarity that are simultaneously grassroots but global amongst feminist activists and collectives.

In doing so, we are following in the footsteps of pioneering feminist film collectives from the past, from the Berwick Street Collective – who made the groundbreaking exploration of women’s labour, “Nightcleaning” – to The Sheffield Film Coop, who made “Red Skirts On Clydeside, screening at the festival.

However, this movement that sought to express women’s aspirations, frustrations and emancipation outside the restrictions imposed by the patriarchy, a literal cinema du papa, existed at an international level, from Cine Mujer (with branches in Mexico and Colombia) to Lilith Video in Brazil to Yugantar in Bangelore.

Most of this work was made in the standard 16mm format of the time, which, while it has an undoubted aesthetic appeal, is still relatively expensive, and has become the preserve – indeed, fetish – of the artist filmmaker today. The quickest, cheapest and most direct way of recording reality – and one that has come to dominance today – is digital video, a form that did not exist in the ‘70s.

However, the new technology that had arrived was the Sony Portapak video, which – for all its shortcomings and relative crudity – would be instrumental in recording so much video art and activist activity of the time.

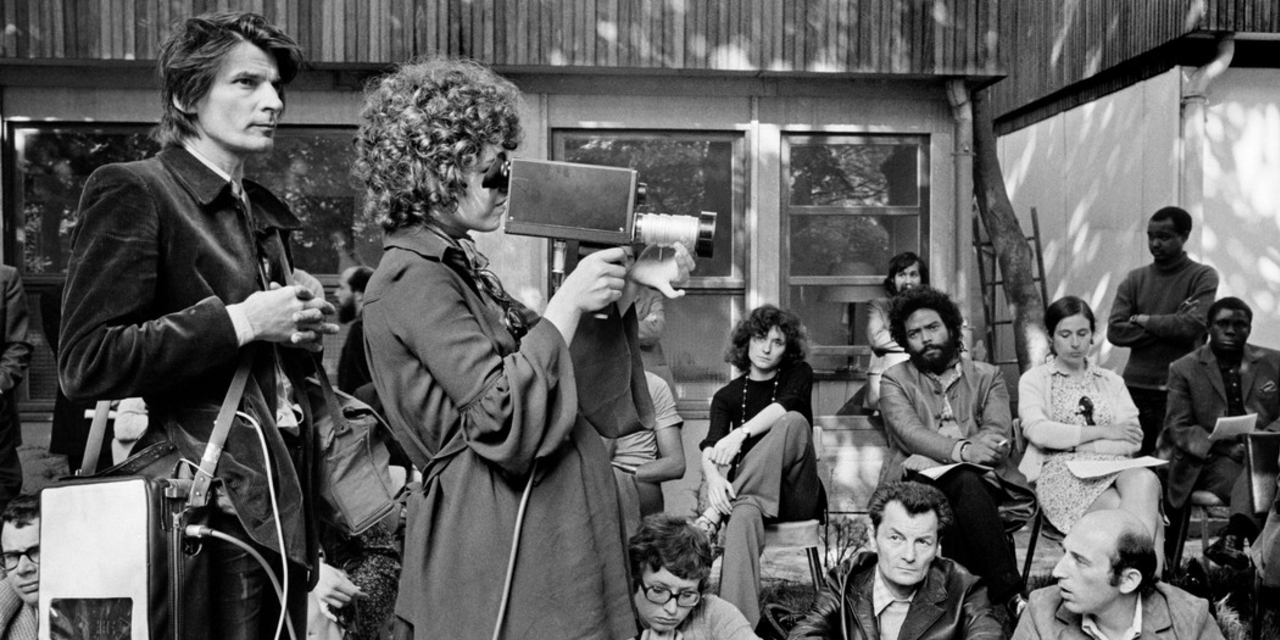

Arguably the first and best feminist activist work of the period would come from Carole Roussopoulos, who bought the second Portapak in France (the always prescient Jean-Luc Godard got in there first) and formed a company Video Out, with her husband Paul. Their first subject was legendary Black Panther activist via the medium of Jean Genet, in “Genet parle d’Angela Davis” (Angela Davis is at Your Mercy), where in the wake of Davis’ arrest by US police, Genet reads a short text condemning the racism of the US and supporting the Panthers. In short, intersectional feminism in action, years before the term was coined.

Genet suggested the subject for the next film, FHARC, Le Front homosexuel d’action révolutionnaire, a loose coalition of lesbian feminists, gay and trans activists whose first demonstration she would record. This is a particularly significant historical document, containing priceless footage of the godfather of queer theory Guy Hocquenghem in action.

Roussopoulos would continue, focusing on more specifically feminist subject matter with her collective les Insoumuses, setting up workshops to spread filmmaking skills amongst other women. Amongst the subjects she would focus on was a sex workers’ strike in Lyon, where, on being harassed by police, they occupied a church and protested, in “Les prostituées de Lyon parlent”. As the film’s title asserts, the subjects are simply granted access to speak, a virtually revolutionary act at the time, where they clearly and cogently lay out their case.

Being more an activist than a cinephile, Roussopoulos didn’t recognise when one of the greatest actresses in French cinema, Delphine Seyrig, started turning up to her classes, though she would herald in a new phase in the collective’s activities. Seyrig had been a darling of the arthouse film set, working with everyone from Resnais to Losey to Bunuel – is there a more iconic image of European arthouse cinema than her immaculate posing in the sublime L’Année dernière à Marienbad? Seyrig, however, had discovered feminism, become outspoken in her activism, and many French male filmmakers and actors were refusing to work with her. While she would progress to make some of the most radical feminist films of the era, with filmmakers such as Chantal Akerman, Marguerite Duras and Ulrike Ottinger, who were all finding radical forms with which to counter what the writer and filmmaker Laura Mulvey had termed ‘the male gaze’, Seyrig’s presence in Les Insoumuses would galvanise the collective and bring it more attention. “Maso et Miso vont en bateau” (Maso and Miso go Boating) was a hilarious detournement of sexism on French TV, with banal clips of pompous French chefs and politicians, all of whom proudly identify as chauvinists, alongside their female apologists, all being roundly ridiculed.

The feature-length “Sois Belle et tais-toi” (Be Pretty and Shut Up) would become their most famous work, utilising Seyrig’s contacts to marshall actresses from Jane Fonda to Maria Schneider to Jenny Agutter, amongst many others, to provide devastating accounts of the sexism they had endured within the film industry. In the era of MeToo, this film could not be more relevant, and it’s gratifying that due to the efforts of the Simone Beauvoir Foundation, these films are now more visible than they have ever been, and finding receptive new audiences. The problems that they address are ongoing, and we hope that the new films presented at the festival continue the struggle and maintain this tradition of radical critique.